What Does Canada’s Announced Nature Accountability Bill Mean for ENGOs?

Nicola Protetch and Mia Tran, University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law (Common Law)

What is Canada’s proposed Nature Accountability Bill?

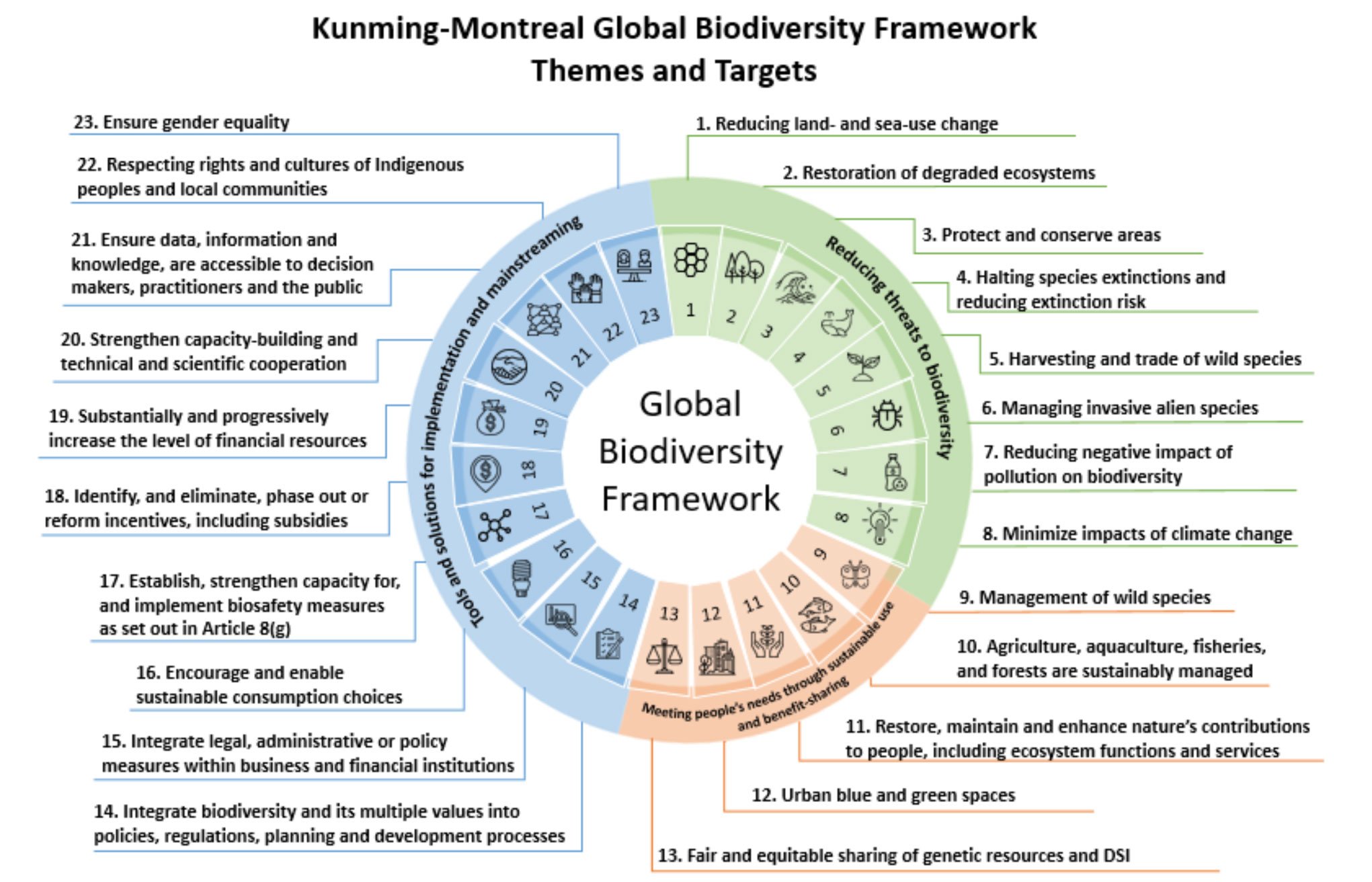

Inspired by the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, Canada’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change, Steven Guilbeault, announced in December 2023 that the Canadian Government is committing to introduce a nature accountability bill in 2024 [1]. The bill would establish a Federal accountability framework for Canada to fulfil its nature and biodiversity commitments under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). The GBF was adopted at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2022 and sets an ambitious pathway with 23 global targets that Parties must urgently meet to halt and reverse biodiversity loss to put nature on a path to recovery by 2030, and life in harmony with nature by 2050.

The nature accountability bill would include concrete steps for the Federal government to implement commitments under the GBF, including a requirement to develop Canada’s 2030 National Biodiversity Strategy (NBS), and report on the implantation process. Thus far, Canada has released a process to develop the 2030 NBS and a Milestone Document that provides a framework for the final NBS, including initial implementation plans for the 23 targets. While the public awaits the introduction of a nature accountability bill before Parliament, this blog post examines the existing constitutional framework to meet the GBF, and will address what is within federal jurisdiction, and the limitations for consistent, national action.

Schematic of the KMGBF goals and targets from Toward a 2030 Biodiversity Strategy for Canada: Halting and Reversing Nature Loss (Environment and Climate Change Canada, May, 2023).

What is Biodiversity and Why Does it Matter?

Biodiversity is the variability of life, including diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems. It is an essential feature of ecosystem resilience, integrity, and function, and has increasingly been of focus for both mitigating and adapting to climate change. Biodiversity is also essential for supporting human and societal needs, such as food and nutrition, medicines and pharmaceuticals, and water filtration.

However, up to a million species globally are threatened with extinction, and the condition and extent of natural ecosystems have declined by an average of 47% from their earliest estimated condition [2]. Canada is experiencing negative impacts from biodiversity loss and climate change at an accelerated rate. Studies have found that the north is heating at four to six times the rate of the rest of the world [3], leading to increased forest and invasive species, and health concerns related to climate change.

Indigenous Nations across the country are particularly vulnerable and adversely impacted by climate change and loss of biodiversity because it increases health risks, disrupts food systems, and adversely affects traditional knowledge and culture. Summer 2023’s increased forest fires in the north further highlight how vulnerable Indigenous and other remote communities are to the impacts of climate change [4].

The Environment and Canada’s Division of Powers

Canada’s federalist system creates a division of legislative powers between the two branches of government (federal and provincial/territorial) that makes regulating and addressing large-scale issues like biodiversity and the environment complicated. The Canadian Constitution Act 1867 [5], distributes legislative powers between the federal government, provinces, and territories under sections 91 (federal) and 92 (provincial), conferring them powers to make laws and policies that apply to public (Crown) lands and resources. The environment is not mentioned in sections 91 and 92, so is left to be legislated under specified subjects under the two heads of power. This complicates comprehensive, national biodiversity conservation because most land and land management, including 89% of natural assets (ecosystem goods including natural resources) are under the legislative authority of the various provinces [6].

Under the Constitution Act, 1867, Canada has jurisdiction over environmental matters that correspond to “Sea Coast and Inland Fisheries [7],” “Navigation and Shipping [8],” federal Crown property, and Indigenous reserve lands, except where a governance agreement exists that allows a First Nation to govern their reserve land under their authority and law [9]. Additionally, the federal government has legislative authority over ocean mammals, and migratory birds [10]. Federal legislation on the environment includes the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) [11], Species at Risk Act (SARA) [12], and the Canada National Parks Act [13], the Fisheries Act [14], and Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act [15]. However, these laws have limited scope that fit within the divisions of powers.

Decisions made by the Supreme Court of Canada have found that Canada can also use its criminal law powers [16] and the National Concern Branch of Peace, Order and Good Governance (POGG) [17] to legislate on the environment, in limited and case-specific circumstances. These powers also come from the federal branch of powers under the Constitution Act. The Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act case relied on the POGG powers of Canada and found that global warming causes harm beyond provincial boundaries and is a matter of national concern. Without legislation that could put a limit on the provinces’ greenhouse gas production would leave no protection for Canadians from the harms of global warming [18]. Likewise, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act relies upon Federal Criminal Law Powers to prohibit, regulate, and sanction certain toxic substances. The Supreme Court found in Hydro Quebec that the Criminal Law powers applied and could be used to prohibit “specific acts for the purpose of preventing pollution or, to put it in other terms, causing the entry into the environment of certain toxic substances [19].”

Provincial Powers and the Environment

The legislative authority of the Canadian provinces extends to many environmental issues under their property and civil rights power and matters of a local or private nature within the province [20]. The legal authority exercised by these governments over terrestrial, marine, and freshwater species and ecosystems largely originates from land ownership. Section 92 of the Canadian Constitution outlines sixteen exclusive heads of power granted to the provinces, including the enactment of laws related to the management and sale of Provincial Crown Lands and forest resources, administration of justice, punishment for provincial offenses, and matters of local or private nature. Further, through an amendment to the Constriction Act 1982 [21], section 92A designates to provinces exclusive jurisdiction over the development, conservation, and management of non-renewable natural resources and forestry resources within their territories.

What does this mean for biodiversity protection?

Considering Canada’s modern tradition of cooperative federalism and its complicated division of powers, what does this mean for a coordinated biodiversity conservation effort under Canada’s proposed accountability bill, and how can provincial actors prepare to support and collaborate under the new law? Federal lands include but are not limited to: Canada’s oceans and waterways, national parks, military training areas, national wildlife areas, and Indigenous reserves who haven’t opted into a legislated land management protocol. Private property and lands under provincial jurisdiction make up most of the lands in Canada. Additionally, the territories are undergoing a process to have jurisdiction and authority over territorial lands, rather than the federal government [22].

This limited federal jurisdiction over much of Canadian land and law-making capacity means that the future bill is less of an authority on land-use, and more a map and strategy to be accountable to Canada’s 2030 Targets, and 2050 vision. The Milestone Document that outlines Canada’s 2030 vision is inspired by a vision of cooperative federalism—a concept of federalism based on the provinces and federal government working in a collaborative way of sharing jurisdiction as much as possible. Ultimately, like monitoring species at risk, federal authority is ultimately limited in scope, and much will depend on the provinces and territories. With the announced nature accountability bill, environmental organizations across the provinces could anticipate an increase in coordination efforts, funding, and strategizing. The federal government wants a “whole-of-government approach,” and “whole-of society approach” while “recognizing, upholding, and implementing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and advancing reconciliation.” The new bill and Canada’s coordinated efforts to implement the 23 GBF Targets are laudable, but not the end-all, be-all for biodiversity conservation. Rather, this is an opportunity for local actors, Indigenous Nations, municipalities, and ENGOs to step forward in a best-effort approach to attain funding, collaboration, and cooperation with the federal government in a foot-forward effort to save biodiversity across Canada.

Conclusion

The forthcoming nature accountability bill is intended to have a similar logic to the Federal Government’s 2021 Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act. Both bills pertain to keeping with international targets and UN commitments, include 2030 and 2050 targets, and include implementation and target recording. The Accountability Act explicitly enshrines the 2015 Paris Agreement into legislation but allows for adaptation and improvements to emissions controls [23]. The nature accountability bill would presumably do something similar with the Kunming-Montreal GBF.

One benefit of the Accountability Act is that it mandated the Federal government to break down their national targets into annual targets with annual actions to stay on track [24]. Carbon emissions and biodiversity protection are both multijurisdictional and need collaboration between the Federal and provincial heads of government. Both also require large-scale change across the country, with long timelines to actualize targets. The Accountability Act also provides an analysis that can be overseen and reported on by the Auditor General, providing oversight and vision for target implementation. The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development at the Office of the Auditor General has begun reporting on existing biodiversity commitments and trends and found Federal action wanting.

While the announced nature accountability act may not lead to drastic change in provincial laws, it will compile Canada’s international commitments, targets, and action plans in comprehensive, enshrined legislation. The mandatory reporting will allow local ENGOs to better hold the federal government accountable to their targets, and incentive provincial governments to set ambitious and transparent targets to better protect nature and biodiversity.

References

1. Natasha Bulowski, “Nature protection targets to become law”, The National Observer (12 Dec 2023), online: <https://www.nationalobserver.com/2023/12/12/news/nature-protection-targets-become-law>.

2. “Milestone document” Government of Canada, online: <https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/biodiversity/national-biodiversity-strategy/milestone-document.html>.

3. Mika Rantanen et al, “The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979” (2022) 3:168 Commun Earth Environ.

4. Liny Lamberink, “The Arctic is warming 4 times faster than the world. What does that mean for the N.W.T.?” (28 Nov 2022), CBC online: <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/arctic-warming-dehcho-region-1.6664273>.

5. Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3, s 91, reprinted in RSC 1985, Appendix II, No 5 [Constitution Act].

6. Justina Ray, Jaime Grimm & Andrea Olive, ‘The biodiversity crisis in Canada: failures and challenges of federal and sub-national strategic and legal frameworks’ (2021) 6 FACETS 1044 at 1045-1046.

7. Ibid, s 91(12).

8. Ibid, s 91(10).

9. Ibid, s 91(1A); First Nations Land Management Act, SC 1999, c 24; Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management Act, SC 2022, c 19, s 121.

10. Supra note 6 at 1045-1046.

11. Canadian Environmental Protection Act, SC 1999, c 33.

12. Species at Risk Act, SC 2002, c 29.

13. Canada National Parks Act, SC 2000, c 32.

14. Fisheries Act, RSC 1985, c F-14, s 2.1.

15. Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, SC 2018, c 12, s 186.

16. Supra note 5 s 91(27).

17. Ibid, preamble to s 91.

18. References re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2021 SCC 11, para. 191

19. R. v. Hydro-Québec, (1997) 3 SCR 213, para 130.

20. Supra note 5, sections 92(13) and 92(16).

21. Constitution Act, 1982 (being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK) 1982, c. 11, s. 35(1)) [Constitution].

22. The NWT and Yukon have signed devolution acts to assume more control over the territories’ lands and resources. See: Yukon Act, SC 2002, c 7; Northwest Territories Devolution Act, SC 2014, c 2. Nunavut parties and the Crown signed the Nunavut Lands and Resources Devolution Agreement on January 18th, 2024, to come into force in 2027.

23. See Canada’s most recent 2050 net-zero emissions plan here.

24. Rosa Galvez “A Short Guide to the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act (CNZEAA)”, online: < https://rosagalvez.ca/en/initiatives/climate-accountability/short-guide-to-the-cnzeaa/>.